In 1997 the recently-formed Indy Racing League was making its first foray into sanctioning an Indianapolis 500 with formula cars powered by a new low-tech spec: naturally-aspirated, production-based, 4-liter V8s. Nobody expected much, as the season-opening races had been judged a disaster by Indy Car pundits and purists, many of whom sided with the rival Championship Auto Racing Teams (or CART), an organization of racers who boycotted the Indy 500, ultimately to its own peril and obsolescence.

History shows now that—by virtue of its symbiotic relationship with the Indianapolis Motor Speedway and its crown jewel, the 500—the IRL won and CART lost (and actually went bankrupt twice, before deep-sixing for good). But in 1997, that eventuality wasn’t so clear. Indeed, at the IRL’s 1997 Phoenix race (contested weeks before IMS opening its gates for Indy 500 time trials), so many engines blew up nobody was sure the race would go the 200-mile distance. Due to the flurry of caution laps based on all the carnage, the race’s average speed was about the same leisurely pace one takes on I-10 and doesn’t worry about getting pulled over by Johnny Law.

In the press room at that year’s Long Beach Grand Prix (sanctioned by CART), over the din and whine of expensive turbocharged engines spooling up and down the race track, I heard a horde of motorsports journalists queued up in the buffet line, running the IRL Phoenix race up the proverbial flag pole while spooning lasagna into their mugs, all the while blathering that Phoenix was the worst race they had ever seen, and how the Indy 500 was doomed to oblivion.

After enduring that tomato-sauced pockets full-of-shrimp group-think tirade, I got inspired and pitched then-HOT ROD Magazine editor Ro McGonegal on covering the upcoming 500, a race the rag reported on thoroughly in the 1960s, but hadn’t touched with a ten-foot porta-potty plunger in decades. Now was the time to revisit it I suggested. Why? he asked. Because, I explained, for the first time in nearly 90 years, they are hosting an Indy 500 that may not actually finish. The Oldsmobile Aurora and Infiniti engines barely made it 200 miles at Phoenix without their connecting rods defenestrating en masse. There is no guarantee anybody is gonna turn 500 miles at Indy, without getting out and pushing their impuissant vehicles.

So he said go and file a report. I went—and was touched to my soul, if to my toenails as so as I saw that back stretch where Vukovic bit it in 1955—and wrote too many words. The race went the distance and Arie Luyendyk won. But before that, minutes before the start, as Chris Economaki took me on a spontaneous tour of Gasoline Alley, I knew the Indy 500 was bigger than any one race, much less any one sanctioning body, so I wrote an entire history of the event. To no avail: My enthusiasm for the race never made it past the suits at Petersen Publishing. HRM never ran it. But CLUNKBUCKET knows…and on this, the eve of this weekend’s 95th Indy 500, allowed for the posting of excerpts from the retrospective that others ignored.

So he said go and file a report. I went—and was touched to my soul, if to my toenails as so as I saw that back stretch where Vukovic bit it in 1955—and wrote too many words. The race went the distance and Arie Luyendyk won. But before that, minutes before the start, as Chris Economaki took me on a spontaneous tour of Gasoline Alley, I knew the Indy 500 was bigger than any one race, much less any one sanctioning body, so I wrote an entire history of the event. To no avail: My enthusiasm for the race never made it past the suits at Petersen Publishing. HRM never ran it. But CLUNKBUCKET knows…and on this, the eve of this weekend’s 95th Indy 500, allowed for the posting of excerpts from the retrospective that others ignored.

And so it goes: This week the New Yorker has run a ten-page feature on the most famous face in IndyCar racing, Danica Patrick. The thrust? How she is leaving the open-wheeled machines for the perceived greener pastures of NASCAR.

Thirteen years after my initial jettisoned-piece for HOT ROD (entitled “500 And More: A Secret History of Americana, The Indy 500 & Human Nature”) and the fourth estate still isn’t listening to the thesis that Indy has a gestalt and is bigger than any of its parts, no matter how one stacks ’em.

500 And More: A Secret History of Americana, The Indy 500 & Human Nature

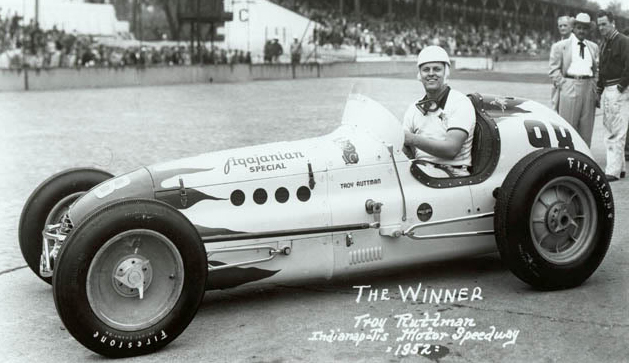

1997– It’s the last days of May and in Lake Havasu, Nevada Troy Ruttman, winner of the 1952 Indy 500, lie dying. And even as death goes, this is particularly excruciating. Ruttman is suffering from lung cancer, and it is slowly, inexorably carving the vitality out of his massive, leviathan frame.

It’s kind of ironic. Because at his zenith, when showcasing his instinctual talent for evading and outrunning anything in his path, Ruttman absolutely pissed on death–not that he didn’t acknowledge it: His susceptibility to ulcers and his penchant for vomiting before climbing into his race car are well documented. Regardless, his legacy it that of the conqueror of the dusty, dirty bullrings and paved ovals across America. “Ruttman backs down for no one,” fellow ace Duane Carter once explained. But, finally, there was one thing he couldn’t outrun, one thing that he backed down from. Because cancer always wins. Eventually.

And at age 67, Ruttman took this mortal coil’s last lap on Monday, May 19, 1997–one week before the 81st Indianapolis 500 went green.

“He was an honest-to-goodness natural born talent,” recalls Chris Economaki, esteemed Editor/”Publisher Emeritus” of National Speed Sport News, who is soaking up the ambiance of his 50th 500 as a reporter. Economaki reminisces while leaning against the guardrail on the Indianapolis Motor Speedway Pit Row on Tuesday, May 27. Coincidentally, it is the morning of Ruttman’s funeral AND it is also half an hour before the Restart of the rained-out 81st Indianapolis 500. Both events are scheduled to transpire at 11:00 AM. Pre-race pandemonium is in full effect on Pit Row but the somewhat gnomeish yet avuncular Economaki is nonplused by the towering blitzkrieg of race teams, Beta-cam toting electronic media and celebrities. “Troy Ruttman never really knew what ability he had or where he got it,” Chris calmly reflects while somebody whisks by on a modified golf cart with a set of slicks in tow. “It was congenital, it was God-given. He was a natural in the car.”

“He was an honest-to-goodness natural born talent,” recalls Chris Economaki, esteemed Editor/”Publisher Emeritus” of National Speed Sport News, who is soaking up the ambiance of his 50th 500 as a reporter. Economaki reminisces while leaning against the guardrail on the Indianapolis Motor Speedway Pit Row on Tuesday, May 27. Coincidentally, it is the morning of Ruttman’s funeral AND it is also half an hour before the Restart of the rained-out 81st Indianapolis 500. Both events are scheduled to transpire at 11:00 AM. Pre-race pandemonium is in full effect on Pit Row but the somewhat gnomeish yet avuncular Economaki is nonplused by the towering blitzkrieg of race teams, Beta-cam toting electronic media and celebrities. “Troy Ruttman never really knew what ability he had or where he got it,” Chris calmly reflects while somebody whisks by on a modified golf cart with a set of slicks in tow. “It was congenital, it was God-given. He was a natural in the car.”

It is overcast at the Speedway and the skies seem to be smeared with Vaseline, but Economaki’s memory is as clear as Heaven’s Harpsichord. “He blew a tire here one year, spun around, and came into the pits with a flat right rear tire. And under his yellow flag he was back out and everybody’s wondering, ‘Wh-wh-why is it yellow? Where is it? What’s wrong?’ He was in and gone.

“He was a born driver. He never got better. He was already that good.” I ask Economaki–the only reporter in the press room this weekend who actually used a typewriter instead of a personal computer–if Ruttman’s passing signifies the passing of an era. “Oh yes…yes,” he mutters in a pitch a few steps above “Middle C” on a piano. He is shaking his head double time, like a dime store chihuahua in the rear window of a ’66 Impala on Whittier Boulevard. “Oh yes.”

Continue reading “500 And More: A Secret History of Americana, The Indy 500 & Human Nature”

Cole Coonce will come around these parts with more screeds now and again. For a great deal more of Coonce in book form – proceed if you dare to the TOP FUEL WORMHOLE

To say that the IRL “won” the battle with Champ Car is slapping some pretty garish lipstick on an awfully ugly pig-by the time the two series returned to one, the IRL had long since forgotten the ‘No Furriners, Low Budget Series’ that Tony George and A.J. Foyt dreamed of, TG had lost 600 million dollars and had been fired by his own family, viewership was (is) in the crapper, the Indy 500 was (is) a disappearing shadow of its former self (I don’t think the stands could be any emptier for qualifying weekend) and the most exciting thing to happen in the series in years is a mediocre woman driver (finally) being booed for being a prima donna. Trust me-the only ‘winner’ here is Gene Simmons for being awarded that ridiculous marketing contract.

But yeah, once again I’m setting aside 4 hours today to watch the damn thing. Kinda’ sad, I know, but what are you going to do. Happy racing.

You are right. There are no winners in this high-stakes war of attrition. At best, it was a Pyrrhicc victory. Can Indy make itself relevant and essential again? Maybe. Doubtful. I watch anyway.